Lower Rockridge — what I call Baja Rockridge — is changing. Once rooted in relationships, it’s becoming more and more defined by transactions. Its blend of homes, landscapes, and street life once inspired national movements like New Urbanism and the walkable cities movement. That balance, shaped by geography, architecture, and history, is now under threat.

Real estate brokers are buying modest homes, expanding their square footage, and erasing the very details—gardens, architectural features, and open spaces—that gave the neighborhood its soul. In their pursuit of profit, they disrupt the long-cultivated relationship among people, nature, and architecture.

To preserve what makes Rockridge special, we need to understand its “secret sauce”: a delicate mix of physical form, architecture, landscape, and culture.

Built quickly after the 1906 earthquake, Rockridge wasn’t planned on a perfect Berkeley-style grid. Instead, its layout followed rail lines that ferried working-class commuters to San Francisco. The result is a neighborhood of quirky five-point intersections, irregular street widths, and an almost improvised urban character.

These odd patterns also led to irregular, often small, lots. Houses are packed tightly, with setbacks and yard sizes that vary dramatically, giving each block its own rhythm.

Architecture and landscape add the third dimension. As a teenager, I fell in love with California bungalows — especially their coffered ceilings, built-in hutches, fireplaces, and formal dining rooms. In the late 1970s, many families rejected suburban sprawl and instead sought homes with quirks and history.

At monthly soup nights on Boyd Street, I get to wander into lovingly preserved homes with compact, human-scaled layouts — living room, dining room, kitchen, and small bedrooms. These spaces reflect a time when gathering by the fireplace or dining with fine china was part of everyday life.

What I cherish most are the intimate living and dining rooms, often framed by fine woodwork and rich tile. These elements evoke what the Danes call hygge — a deep sense of warmth and coziness that makes a house feel lived-in and timeless.

Walking through Rockridge, I think of my mother, or the characters in Thirtysomething, always renovating their old home but never quite finishing. That show captured a generation’s yearning for homes with soul — just like those found here.

Sadly, many of these interiors are now being gutted by flippers. Original plaster walls are replaced with sheetrock, rooms are merged into oversized, echoey spaces, and everything is painted white. These houses become Instagram-ready but emotionally hollow. They may sell quickly, but they don't foster community — and they certainly don’t foster soul.

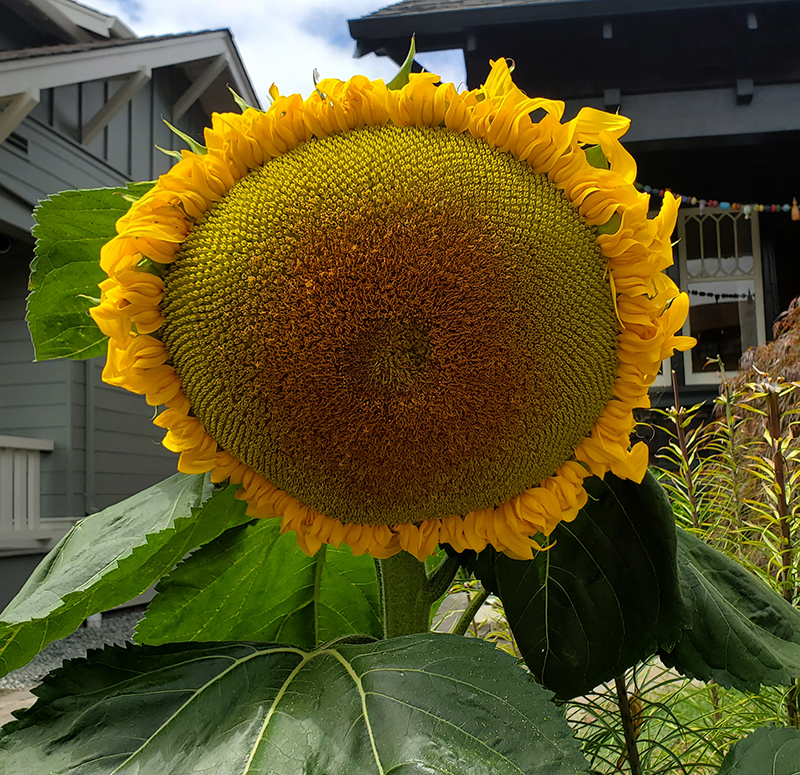

Landscape as Self-Expression

Rockridge bungalows were designed to connect with nature. Their generous front porches encourage indoor-outdoor living and act as visual invitations to the neighborhood.

Our Mediterranean climate allows for stunning gardens — French lavender, agaves, California poppies — all growing together in colorful, eclectic displays. With small yard sizes and a wide plant palette, residents treat their gardens as creative canvases. One yard may be meticulously maintained, another wild and spontaneous, a third barren but artfully spare. Our own has a prairie vibe. Each tells a story and adds texture to the streetscape.

But even these landscapes are under threat. Porches are being enclosed, gardens ripped out for wide driveways and oversized SUVs. Many old homes never had driveways or shared narrow ones between houses. But the rise of car culture means new residents often experience the neighborhood through windshields rather than walking.

As social media and car convenience take priority, the subtle details that once defined Rockridge — its porches, pathways, gardens — are being lost. Today’s “LA Creep” homes offer comfort without character. People move in not for community or craftsmanship, but for status and convenience. And so, the balance between people, place, and architecture is steadily sacrificed.

To protect Rockridge’s identity, we need to codify its character — a “Cozy Specific Plan” that prioritizes human connection, architectural heritage, and landscape beauty over transactions. Yes, more housing is needed, but it must respect the balance that gives this neighborhood its soul.