Ask most people why they live in Rockridge, and you will quickly detect a group of common reasons: wonderful and architecturally interesting housing stock, a vibrant pedestrian-oriented shopping and dining “main” street, great public and private transportation options for commuting near and far, good schools, and a wonderful sense of community. If you had asked a Rockridge resident in 1920 why they lived here, you would have heard much the same thing.

How has the character of the neighborhood managed to stay so stable as well as vibrant for over 100 years? The secret lies in the most interesting variable, the remarkable and diversely creative people who choose to live here, and something called a “Natural Cultural District.”

In 2007, Professor Mark Stern, Co-Director of the Urban Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote a paper called “Cultivating Natural Cultural Districts” wherein he defines the phenomenon as places with significant economic, environmental and social benefit.

Natural cultural districts are social networks built by creatives of all types: “cultural creatives” as defined by co-authors Paul Ray and Sherry Anderson in The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World — representing the American creative industry workforce in science, engineering, architecture, design, education, arts, music and entertainment. Based on research by Richard Florida, author of Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life, and its sequel Flight of the Creative Class, their presence is directly tied to economic prosperity. Florida notes in his book, “What is striking about this phenomenon is that it occurs without policy intent.”

Rockridge has always been home to a large number of creative types: published and prize-winning authors in all genres; actors, writers, composers, and Oscar winning filmmakers with their own IMDB pages; local, national and internationally known artists on the annual Pro Arts tour; nationally acclaimed architects and designers; journalists from Print, TV and Radio; sports figures; and business innovators.

Rockridge Celebrities and Influencers

Some local notables have been internationally respected, such as vocal coach, Judy Davis, who helped artists as diverse as Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand (her lifelong friend), Dolly Parton, and the Rolling Stones. They would often come to her studio door on College Avenue and her home studio on Ivanhoe.

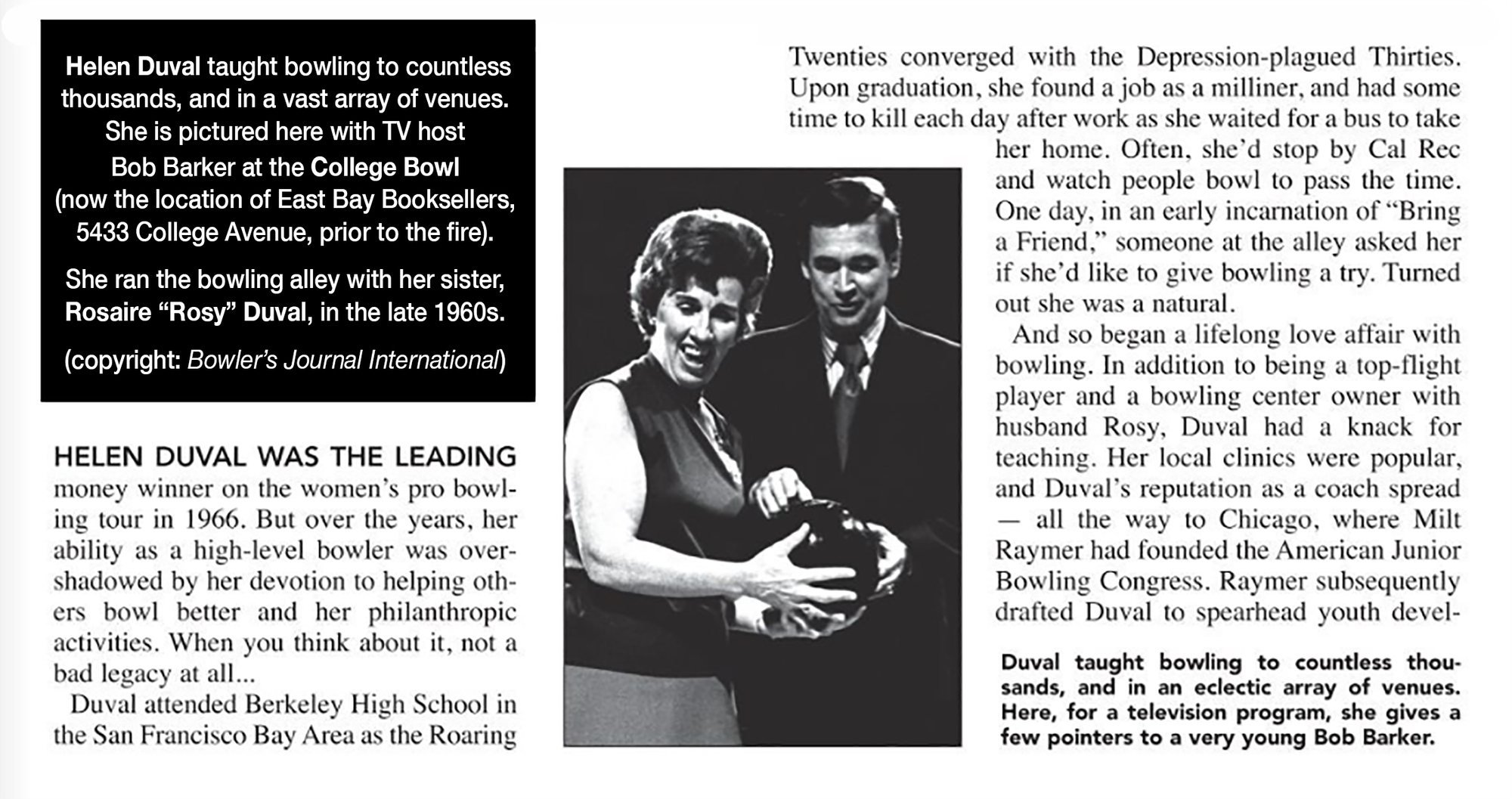

Other notable residents include Helen Duval (pictured above with Bob Barker at College Bowl), a foundational figure in women's professional bowling and a USBC Hall of Famer; and Peter Voulkos, known as the Father of the American Clay Revolution or Contemporary American Ceramics, a ceramicist and sculptor who elevated clay from craft to fine art. Voulkos influenced generations of artists through his teaching at UC Berkeley and the Otis Art Institute. His works can be seen in the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian, in the sculpture garden of the Oakland Museum of California, and numerous museums worldwide.

Natural Cultural Districts are also distinguished by what all these creatives do for the community. In this respect, Rockridge has been a hub of innovative thinking, largely shaped by the neighborhood organization RCPC, established in the early 1970s by various community groups when the area was known as the Chimes district.

Some of the early initiatives included:

- This neighborhood originated the C-31 special pedestrian-oriented retail commercial zoning (now CN-1) in 1972. Don Kinkead, who later founded the Rockridge News, became an important community voice for the ongoing need to defend the designation. Rockridge has been a major economic engine for all of Oakland ever since. And, in response to requests, local activists assisted five other Oakland neighborhoods in adopting the pedestrian-oriented retail shopping zoning for their own economic success.

- Malcom Singer and other Rockridge neighbors pioneered Casual Carpooling in the late 1970s when Caltrans established the first carpool lane on the Bay Bridge. They began flagging commuters for a ride to San Francisco at the corner of Claremont and Hudson, at the entrance to hwy 24, to help commuters save on the bridge toll. The practice was made official in 1979 when Caltrans posted the first sign at the same corner that said “Carpool Pick Up Here.”

- After the Oakland Firestorm in 1991, former RCPC Chair, Brooke Levin, then an aide to Mayor Elihu Harris, facilitated the creation of the Disaster Recovery Center at the vacant Safeway on Claremont Avenue in response to the loss of 3,000 units of housing. This center was the first in the nation to aggregate all the necessary governmental and private sector services, and now serves as the model for FEMA disaster recovery centers nationwide.

- Rockridge is the only neighborhood in the United States to ever fund and build its own branch library. To accomplish this, neighbors organized and ran a successful volunteer political campaign to form a special taxation district. Neighbors for a Rockridge Library, led by Nancy Dutcher, was formed, and became the official fundraising and advocacy group. In 1996, the organization was renamed Friends of the Rockridge Library (FORL) soon after the branch moved to its current location on College Avenue; it became a nonprofit in 2011.

- In 1997, RCPC Board Member Dan Pitcock came up with the idea of turning the former Caltrans heavy equipment staging area into a dog park. The Hardy Dog Park overcame a number of obstacles to become the first dog park in Oakland, setting the stage for several new dog parks to come in later years around the city. Steve Costa, Eileen Fitz-Faulkner, and Theresa Nelson were the co-chairs of what was then the Parks Committee and did all the organizing and fundraising (almost $3 million now and counting) to build the park and the play structures. This group formed Friends of the Rockridge-Temescal Greenbelt (FROG) which continues to raise funds for improvements.

- Rockridge neighbors partnered with six other neighborhood organizations from Oakland and Berkeley in 2006 to form the “Fourth Bore Coalition” nonprofit in order to sue for environmental mitigations when Caltrans built another bore through the Caldecott Tunnel on Hwy 24. The coalition’s vice-chair Ronnie Spitzer, and lead attorney Stuart Flashman, led the coalition to a successful litigation — securing a $3M settlement for environmental improvements at Claremont Middle School and Chabot Elementary School, along with traffic-flow improvements.

For generations, people here have imagined what their community could be, and worked together to make it happen. That shared creativity and civic spirit is why Rockridge has stayed vibrant for over a century, not just as a place to live, but as a community shaped by the people who call it home.